A js developer’s view of rust

13 Sep 2019A while ago, I was trying to find something interesting to read about online when I bumped into Rust. Rust is …

“a language empowering everyone to build reliable and efficient software.”

In short, it is a systems programming language. A freaky fast one, at that. It even outperformed C++ in many of the benchmarks tests run by The Computer Language Benchmarks Game (mostly having to do with complex algorithmic tasks like binary trees, etc).

Before I started to delve more into the language itself, though, I searched about to see what people were thinking of it. Rust was created in 2011 and is backed by Mozilla (the not-for-profit). It has a sort of niche group following it consisting mostly of previous C/C++ developers who wanted a break from the null pointer exceptions, undefined behaviors, language complexity, crazy macros — shall I go on? Although Rust is still in its early stages of maturity, it has a website devoted to following its development of game programming, which is pretty sweet. There are even some games that are gathering a lot of buzz and have even been put into the App Store and the Google Play Store such as A Snake’s Tale. Rust even has an AMAZING package manager called crates.io which is comparable to npm and has had almost 1.5 billion downloads to date.

After seeing all of this, I decided that I needed to feed my curiosity and learn Rust’s syntax. I started by reading through The Book — a (mostly) complete walkthrough of Rust’s syntax, idioms, and program structure.

Because I know many c-like languages, the general form of the syntax was simple and easy to grasp. If you are one of those people who use const whenever possible and will punish those who don’t, you’ll love Rust. Its default form of assigning variables makes them immutable.

// Below is an immutable variable

let a = 5;// Below is a mutable variable

let mut b = 5;// General form for variables:

let var_name: type = value;

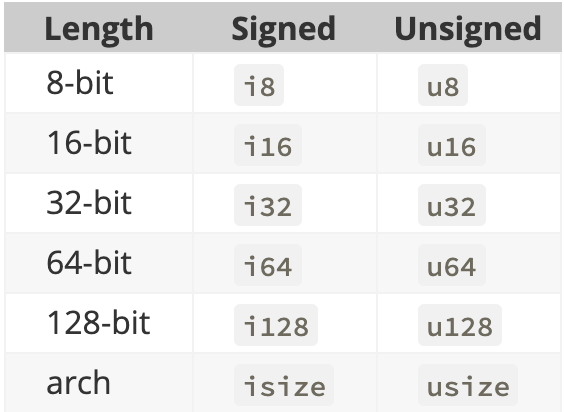

Data types in Rust are straight forward. Integer types consist of 8 through 128 bit unsigned and signed numbers.

There are also immutable array types, characters, &str (references to a list of characters in memory), tuples, enumerations, structs, collections, etc.

Functions are declared using the fn keyword like so:

fn main() {

println!("Hello, world");

}

You can specify return values with the -> symbol and if you are returning a value in the last line of the function, there is no need to include the return keyword.

// returns the 32-bit integer 5

fn my_function() -> u32 {

5

}

I was breezing on through until I hit the concept of ownership. All programs have to manage the way they use a computer’s memory while running. Because Rust doesn’t garbage-collect and programmers don’t have to manually allocate and deallocate memory, memory is managed through a system of ownership.

Here are the rules of ownership in Rust (right from The Book):

- Each value in Rust has a variable that’s called its owner.

- There can only be one owner at a time.

- When the owner goes out of scope, the value will be dropped.

Let’s have an example:

{ // s is not valid here, it’s not yet declared

let s = "hello"; // s is valid from this point forward

// do stuff with s

} // this scope is now over, and s is no longer valid

Here is the jam that I got into when I was first using Rust.

let a = String::from("Hello, world!"); // a is the owner

let b = a; // ownership has changed to b. What is a?

println!("{}", a); // error[E0382]: borrow of moved value: `a`

Because there can only be only one owner at a time, I can’t try to assign the value of a variable to another using the first variable’s name if it was allocated on the heap, like the String type is in Rust. Now, if the variable’s type is a primitive (int, double, bool, etc), doing the reassign will simply copy the value and NOT change ownership.

When referencing a variable, you use the & symbol as in C/C++. The references allow the programmer to take the value without taking ownership. There can be as many non-mutable references as one wants to a variable at one time, but only ONE mutable reference.

let a = String::from("Dude, Rust is sick.");

{

let b = &a; // ok

let c = &a; // ok

}

{

let b = &mut a; // mutable reference. ok.

*b = String::from("Different!"); // change value. ok

}

{

let b = &mut a; // ok

let c = &mut a; // ERROR. Only one mut reference at a time!

}

Even more difficult for me to understand was rust lifetimes which is how Rust can get around using garbage collection. It is also their solution to the all too well known C++ problem of dangling pointers when a variable is “used after free”. I won’t even attempt to explain that concept here. You should read this article to find more.

Overall, I would say my experience with Rust was rewarding. I was able to understand its syntax and style guide easily, although some of the concepts were difficult to grasp at first. I don’t know if this is just me, but even the way the language looks when typed is elegant. It uses functional programming techniques commonly used in JavaScript (filtering, mapping, etc) and its syntax keywords are short and too the point (fn, enum, let, mut, i32, &str, etc.)

Some systems developers are lobbying heavily for Rust to be the next C/C++. I don’t know whether that will happen anytime soon, but one thing is for sure: it will continue to grow and mature. It is backed by Mozilla and has a ‘cult’ following that want to kill off C++.

So there.

Go look at Rust.