A complete approach to neural networks

02 Jan 2020The majority of advances in artificial intelligence in the last half-decade has been in the developing technology of artificial neural networks (ANN).

ANNs are created by programming a computer to loosely model the interconnected brain cells of a human.

An ANN is based on a collection of connected nodes or neurons which represent singular neurons in a biological brain. These nodes are connected through weights which, like synapses in the biological brain, can transmit signals to one another. In an ANN, however, all of these nodes and weights are simply numbers. The calculations that go into producing a single value from an entire artificial neural network is just a series of multiplication and addition operations.

The field of deep learning further explores the world of ANNs by branching off and creating recurrent neural networks, generative adversarial networks, long/short term memory networks, convolution networks, Markov chains, Hopfield networks, and many many more. However, for the purposes of this article (and staying sane), I will go in-depth into the intuition behind deep feedforward neural networks.

Please note if you haven’t read my article on perceptrons, please do! (It’s a fast read and has some info that’ll help with understanding ANNs)

I would also highly suggest reading about Univariate Linear Regression to gather an understanding of mathematical notation for ANNs and Linear Algebra to better understand this article. You will need this information. To get a good understanding of what activation function we use and why, you should read about them here.

It’s Just Addition

Please don’t do what I did and make ANNs out to be difficult. They simply aren’t.

Because an ANN is simply layers of perceptrons, we will look first at what that entails.

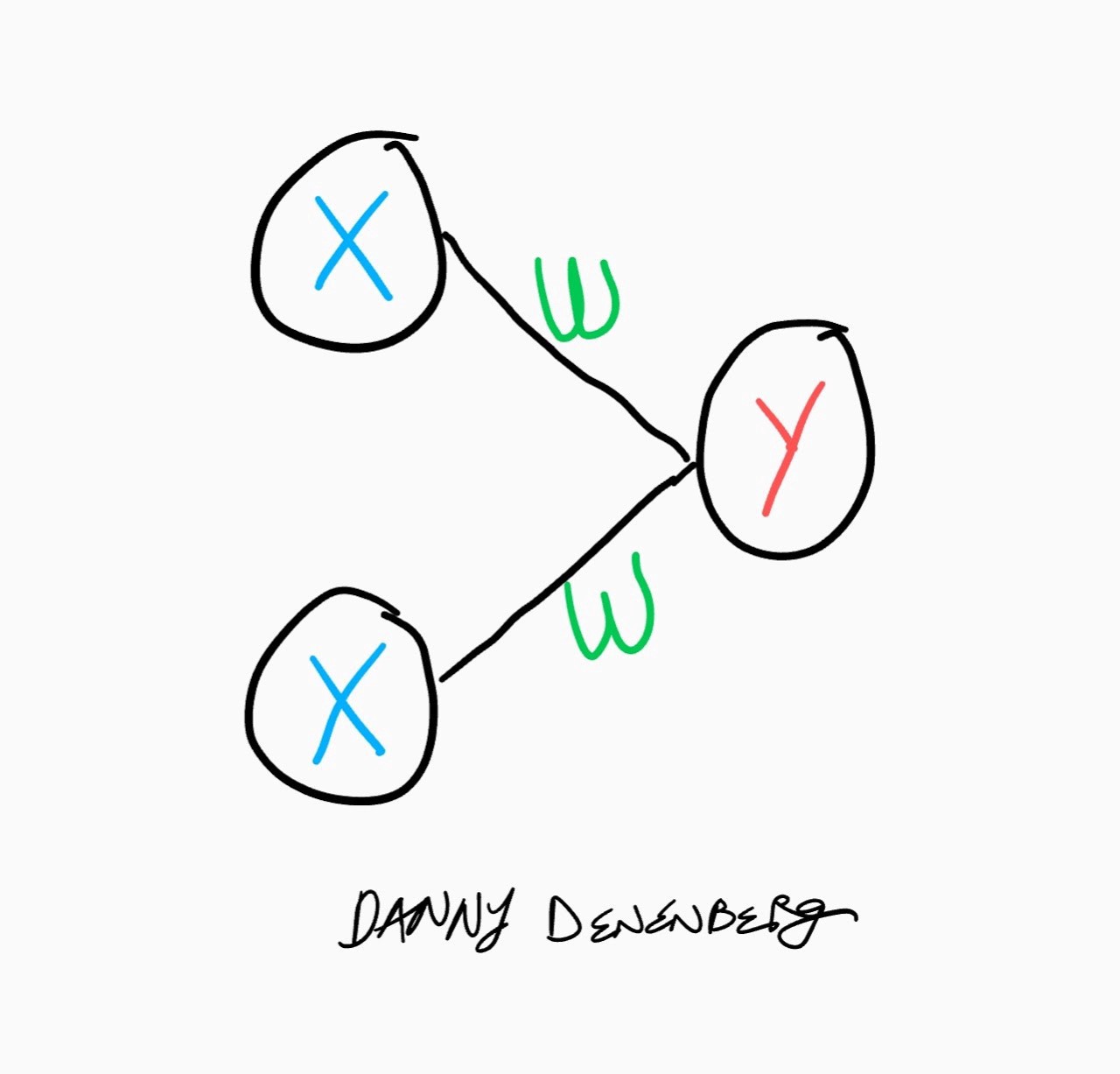

For a refresher, a perceptron has input nodes and a single output node. Each input node is connected by its own weight synapse to the output node. To calculate the output of a perceptron, you take the sum of each input node multiplied by its corresponding weight value.

Let’s take a look at this simple perceptron:

In this case, y is equal to:

!!y=x_1w_1+x_2w_2!!

Or, in a more abstract view:

!!y=\sum^m_{i=0}x_iw_i!!

where m is the number of inputs and i is the specific input and weight specified by its index. this sum is known as the “weighted sum”.

An ANN has **layers **of these perceptrons where output layers can have more than one node. A very simple ANN structure looks like this:

^3 layer ANN drawn on a Pixel 3 XL :)

^3 layer ANN drawn on a Pixel 3 XL :)

This is an ANN with 3 layers. As you can see, there is an input and output layer (column) of nodes, but there is also a 3rd layer in the middle. This is called the “hidden” layer. The node values in this layer are the outputs from the first layer and the inputs to the last layer (outputs). If you add a second hidden layer, the values from the first hidden layer are used in the weighted sum for the second.

You can add as many hidden layers as you want, although the math gets more tedious (not harder!) the further you go.

Let’s Delve

In the depiction above, each node in a certain layer is connected to every node in the previous layer through a synapse/weight. This type of network is known as a fully connected network and is the type of ANN that I will be focusing on in this article.

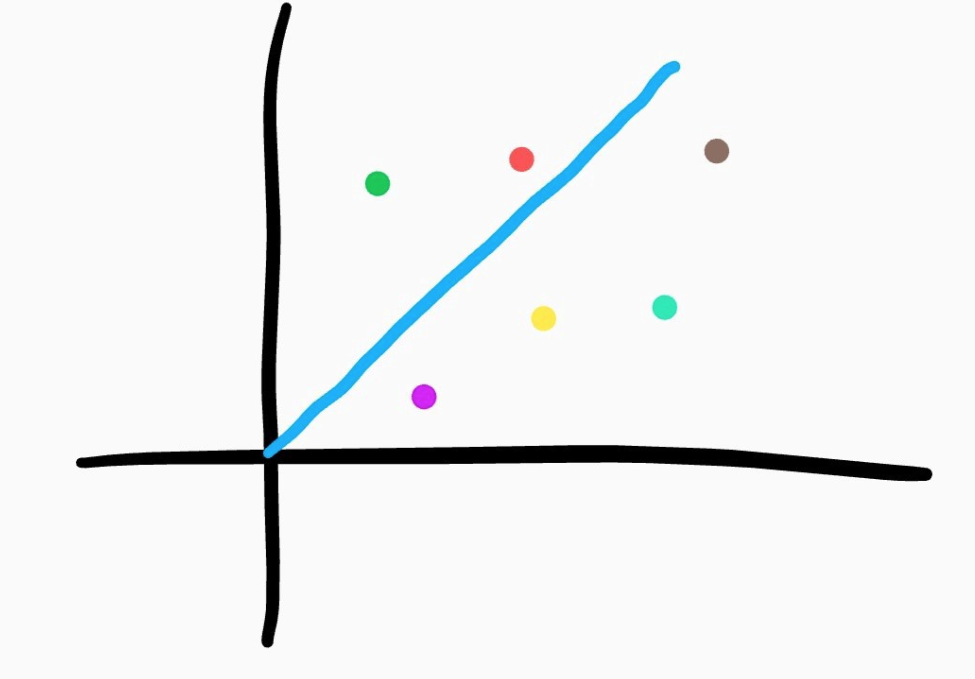

Because of this connectedness, a node’s value, as in a perceptron, is the weighted sum of all of the nodes in the previous layer. However, unlike a perceptron, the weighted sum is not passed through a step function to determine the final value of an output node. It is passed through some activation function that presents some complex mappings between the weighted sum and the node’s actual value. They introduce non-linearity into the network. This non-linearity is extremely important to the network’s ability to learn. It is crucial that the activation function be non-linear or else the entire network can only conform to linear patterns such as a line of best fit.

Boring, linear function

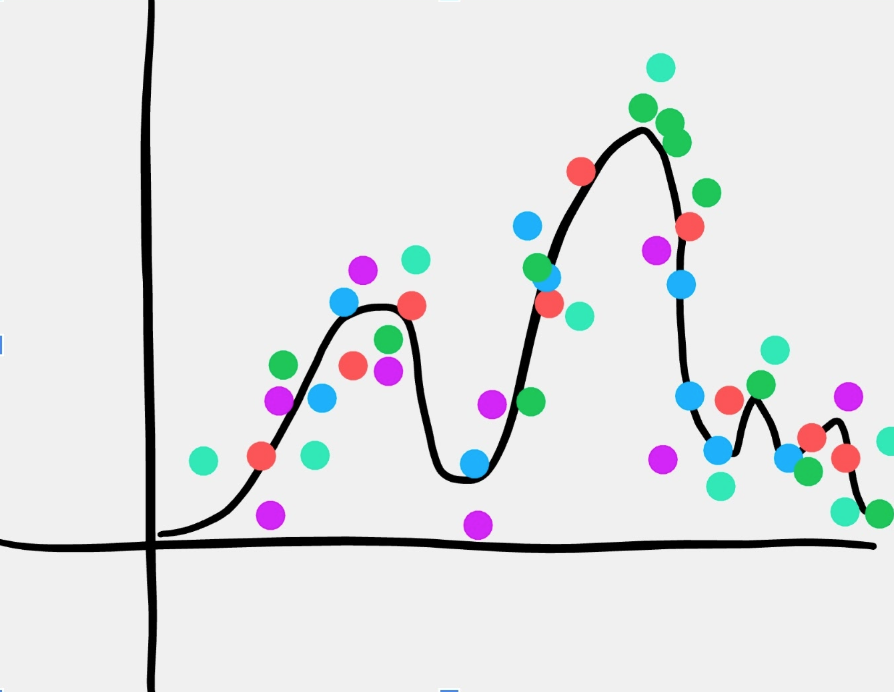

With a non-linear activation function, the ANN can conform to complex $x,y$ mappings like this one:

Super dope, non-linear function

Super dope, non-linear function

I hope you can now understand some of the key differences between a neural network and a perceptron. In the next section, I will go into the concept of forward propagation.

Producing Outputs

Forward propagation is the process of taking input values and propagating them through the network’s layers until you find the final outputs. Basically, it is the process of executing the ‘function’ of the neural network which is to take input values and use weights and non-linear activation functions to transform them into some output values.

For a 3 layer network (depicted here), here is the general set of operations for finding the final outputs:

- Use first layer input values to find the weighted sum for each of the nodes in the hidden layer

- Send the hidden layer weighted sums through some non-linear activation function

- Use these hidden values to find the weighted sum for each node in the output layer

- Send the output layer’s weighted sums through some non-linear activation function — these are the FINAL outputs for the network

Let’s go through all of these steps for our 3 layer network depicted below:

STEP #1

Use first layer input values to find the weighted sum for each of the nodes in the hidden layer.

If we model our inputs (x) and weights (w) as matrices, the math to get to the second layer becomes much more obvious.

Just a quick note about notation:

The weights connecting the input and hidden layers, I will denote as follows: Wᵢₕ

The weights connecting the hidden and output layers, I will denote as follows: Wₕₒ

!!X=\begin{bmatrix}x_1 & x_2\end{bmatrix}!! !!W_{ih} = \begin{bmatrix} w_{11} & w_{12} & w_{13} \\ w_{21} & w_{22} & w_{23}\end{bmatrix}!!

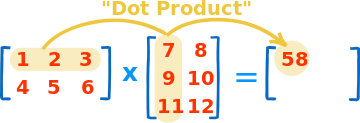

Just for a quick reference, here is how you multiply matrices:

Image from

mathisfun.com

Image from

mathisfun.com

Therefore, to get our hidden layer weighted sum, just multiply (take the dot product of) the input matrix and the weight matrix. The hidden layer nodes are represented by $H$.

!!H{weighted-sum}=X \cdot W{ih}=\begin{bmatrix} (x1w{11}+x2w{21}) \\ (x1w{12}+x2w{22}) \\ (x1w{13}+x2w{23})\end{bmatrix}!!

STEP #2

Send the weighted sum through our activation function.

For the purposes of simplicity, we will be using the sigmoid function. Please read about it here (this article also holds information about other activation functions and their unique uses in ANNs).

For a quick reference, here is the definition for our sigmoid function:

!!\sigma(x)=\frac{1}{1+e^{-x}}!!

Now we can pass our weighted sum matrix through this non-linear activation function and the outputs of this are our values for our hidden layer nodes.

!!H=\sigma(X\times W_{ih})=\begin{bmatrix} \sigma (x_1w_{11}+x_2w_{21}) \\ \sigma(x_1w_{12}+x*2w_{22}) \\ \sigma (x_1w\_{13}+x\_2w_{23})\end{bmatrix}=\begin{bmatrix} h_1 \\ h_2 \\ h_3 \end{bmatrix}!!

STEP #3

Use these hidden values to find the weighted sum for each node in the output layer.

Essentially, we now have to repeat steps 1 and 2 by treating the hidden layer as the input layer.

We can again model the hidden layer and the weights as their own respective matrices.

TK hidden layer and weights as matrices math

And then multiply them to find the weighted sum for the output layer.

!!Y_{weighted-sum}=H \cdot W_{ho}!! !!= \begin{bmatrix} h_1 & h_2 & h_3 \end{bmatrix} \begin{bmatrix} w_{11} & w_{12} \\ w_{21} & w_{22} \\ w_{31} & w_{32}\end{bmatrix}!! !!= \begin{bmatrix} h_1w_{11} + h_2w_{21}+h_3w_{31} \\ h_1w_{12}+h*2w_{22}+h_3w_{32}\end{bmatrix}!!

STEP #4 (FINAL)

Send the output layer’s weighted sums through some non-linear activation function.

To get the outputs for the entire network, we just have to pass the weighted sum for the output layer through our activation function (sigmoid once more).

!!Y=\sigma (H \cdot W_{ho})=\begin{bmatrix} \sigma (h_1w_{11} + h_2w_{21}+h_3w_{31}) \\ \sigma ( h_1w_{12}+h_2w_{22}+h_3w_{32}) \end{bmatrix}!!

And that produces the final ‘outputs’ for our ANN.

We can call this a network that produces two outputs (one for the first output node and one for the second). This concludes the process of forward propagation.

Improving our Network’s Accuracy

Let’s say that we created a neural network to act as an XOR logic evaluator. If it is fed in a 1,0 it should output 1 for true, 0,0 should output 0 for false, etc.

(1,0) => 1

(1,1) => 0

(0,1) => 1

(0,0) => 0

If all of the weights are initialized at *random *in our network and we feed it in a (1,0), there is an infinitesimally small chance that it would actually output the correct answer of 1. In other words, because the weights are initialized at random, the ANN ‘function’ is not correctly defined.

What we need is some way to take our randomly initialized network and optimize it to fit a set of criteria or examples that we provide.

This method of optimization is known as backpropagation and is a central idea to the structure of neural networks even outside of the 3 layer standard.

Before we can begin to optimize our network, we must define a means to tell just how wrong of outputs the network produced.

From the example above, if I fed in (1,0) and the network gave out 0, I need to define just how “wrong” that specific output was.

This is known as defining an error function. Although there are many, complex and interesting definitions, for the sake of taking easy derivatives, I will be using a simplistic version of what is known as squared error.

E = (ŷ — y)²

ŷ is the output that the ANN produced and y is the expected output of the network (a.k.a. the ‘correct’ answer).

So, in the example explained above where (1,0) was inputted and the ANN outputted 0 (the wrong answer), the error would be:

E = (0–1)²

= 1

Now that we have this idea of an error function, we can begin to actually optimize our network’s performance through an algorithm known as gradient descent.

If we take a look at the graph of our error function for a data sample, like the (1,0) above, it would look something like this:

As you can see, the further the outputs from the network (inputs to the error function above) stray from the correct answer, 1, the error grows.

We can also clearly see that the optimum value for the network occurs when the output is 1 because this is the value at which the error is the smallest (0 error). This optimal value happens at the** vertex** of the function — where the slope is zero.

Therefore, because the derivative of a function describes its instantaneous rate of change at any point, the optimal value can also be described as the point at which the error function’s derivative is 0.

!!\frac{dE}{dx}=0!!

This can also be rewritten as

!!\frac{dE}{dŷ}=0!!

This process of finding where the slope of a function is zero in order to find a minimum (or maximum, if the vertex is a high point) is known as minimizing a function. It’s a super common problem in calculus and the real world.

In the function above, it was immediately clear what the optimal value of x was.

In ANNs, however, the error produced is based on large numbers of weights. Each individual weight is an independent variable that affects the error function in its own manner. Thus, using each weight as inputs to the error function, the graph suddenly becomes hugely complex and exists in many dimensions. Below is an example of a simplified error function graphed in 3 dimensions:

As you can see, simply by adding a single dimension, it becomes much more difficult to pinpoint the optimal value by looking at the graph.

TODO: the output that produces the lowest error occurs at the lowest point of the graph. that point is where the derivative is zero (horizontal line). Explain how you can start from anywhere and subtract the derivative and get to the min. Also explain WHY we use this method (b/c there are much more complex error functions that produce 3d, 4d, 5d, etc. graphs — show picture).

Note: This article is not yet done. I put it on my site simply to allow people to learn before the article is written in its entirety.